VICTIMS OF NAZI MILITARY JUSTICE

Hundreds of thousands of people – soldiers, prisoners of war, and civilians – were tried before German military courts during World War II. Until today, little is known about their lives and motivations. Deserters may have been driven by fear for their family’s safety or fear of draconian punishment; political and ideological motives as well as situational factors, such as critical experiences or sheer opportunity, may have played a crucial role. For many, there may have been multiple reasons.

In the following, we document 15 cases of mostly Austrian victims of Nazi military justice. The aim is to depict diverse motivations, biographical backgrounds, and crimes committed. The cases were furthermore chosen to reflect the stories of insubordinate soldiers from all over Austria. It is important to mention this, as for some regions relatively many stories of persecution are known (such as Vienna or Vorarlberg), while there is little or no research covering other regions. This in particular applies to the reliable documentation of events with respective records or photographs.

It is also important to note that the following selection should not be considered representative. The sources available make it impossible to draw quantitative conclusions about the victims’ motivations, let alone their biographies, the circumstances of their actions and their rejectionist attitudes. Nonetheless, the case studies illustrate the multifaceted and criminal nature of a persecution that claimed over 30,000 lives.

»We simply stood on the other side …«

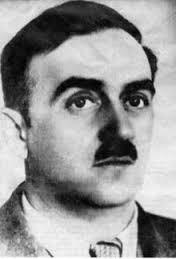

Richard Wadani (* 1922)

Richard Wadani was raised in Prague by his Austrian parents. Already in his youth he began sympathizing with the communists, and he joined their youth organization in the mid-1930s. As a result of the »Munich Agreement«, the family had to leave Czechoslovakia in 1938 and move to »Ostmark«, as Austria was called when it became part of Nazi Germany. Richard Wadani enlisted in the Wehrmacht in 1939 and served as an occupation soldier in the Soviet Union between 1941 and 1944. During this time, he supported partisan groups and thereby put up resistance to the Nazi regime. In October 1944, he defected to American troops on the Western front. He volunteered for the Czech exile army and returned to Vienna in December 1945, where he soon joined the Austrian Communist Party. Until retirement he worked, amongst other things, as a certified physical education teacher and coach of the Austrian national volleyball team. He left the Communist Party following the violent suppression of the »Prague Spring« in 1968. Since the late 1990s, he has provided the victims of Nazi military justice with a voice and a face. In 2009, the National Assembly acknowledged soldiers and civilians who had been persecuted by German military justice as victims of National Socialism. The »Repeal and Rehabilitation Act«, in which deserters and other victims of Nazi military justice were legally recognized as such, as well as the establishment of the memorial on Vienna’s Ballhausplatz can be attributed in part to his remarkable political commitment.

Literature

Koch, Magnus, Rettl, Lisa: Richard Wadani – Eine politische Biografie, »…und da habe ich gesprochen als Deserteur.«, Milena Verlag, Wien 2015.

»… he mostly kept to himself and showed little connection to his comrades.«

Erwin Kohout (1909-?)

On February 7, 1942, a Wehrmacht patrol arrested tailor apprentice Erwin Kohout, who had been born in 1909 in Linz, in his mother’s apartment. He explained that he had no longer felt comfortable with his unit in Ukraine, which is why he had deserted. He had, for example, quarreled with his superior. Although Kohout had abandoned his unit for close to three months, and thus permanently, the military court did not mete out a death sentence, as was the usual practice in such cases. The court gave him credit for the fact that he had not gone into hiding and had not committed crimes while away from his unit. Kohout was deported to the Emsland Camps in the northwest of the »Greater German Reich«, where he was to carry out hard forced labor for ten years. It is not known whether he survived the war.

»If only every decent Christian would save even one single Jew…«

Anton Schmid (1900–1941)

In March 1938, Anton Schmid and his wife Stefanie ran a radio shop in Vienna’s Klosterneuburgerstraße. Not long after Austria’s »Anschluss« to Germany in March 1938, he had helped Jewish friends escape National Socialist persecution. Since 1941, he was stationed in Lithuania as an occupation soldier. Immediately after the German invasion, the SS had begun carrying out brutal killing operations directed mostly against the Jewish population. They were supported by the Wehrmacht, police units, and Lithuanian auxiliary troops. Sergeant Anton Schmid was a witness to these crimes and he decided to help the victims. According to eyewitness accounts, he hid a young Jewish woman, Luisa Emaitisaite, and several other people at his duty station and supplied them with new documents. He also supported the Jewish resistance movement in Lithuania by helping some 300 Jewish men and women escape from the ghetto in Vilnius. Schmid was most probably denounced by two comrades in January 1942. A Wehrmacht court sentenced him to death shortly afterwards. He was shot in Vilnius on April 13, 1942. In 1966, the Israeli memorial Yad Vashem awarded Anton Schmid the honorary title of »Righteous Among the Nations«.

Literature

Wette, Wolfram: Feldwebel Anton Schmid. Ein Held der Humanität, Frankfurt a.M. 2013.

»…that louse Hitler.«

Franz Severa (1912-1944)

The mechanic Franz Severa, who was born in Vienna and raised in a social democratic environment, was a member of the »Socialist Protection League« when he was arrested by the Austro-fascist regime for several weeks in February 1934. In early 1941 – Severa was by then working in an airplane engine factory in Vienna’s Stammersdorf district – a colleague of his filed a complaint against him. Severa had allegedly called Adolf Hitler a »louse«. The presiding judge found that the defendant had »out of base motives deeply insulted« the commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht and Reich chancellor and thereby tried to »undermine the nation’s trust in the political leadership«. After the Gestapo found Marxist literature while searching Severa’s apartment and he was once again denounced for anti-Nazi statements while at the Wehrmacht remand prison X in Vienna-Favoriten, the Division No. 177 court sentenced him to six years and six months in prison. Towards the end of the war, Severa was transferred to punitive battalion 999. He died on the Western front on December 28, 1944.

»Ten more comrades will die with me …«

Johann Lukaschitz (1919-1944)

In January 1944, the Reich court martial sentenced Johann Lukaschitz, an advertising artist who had been born in Vienna in 1919, to death for »failing to report military treason«. Frustrated with the military situation in the fourth year of war and the harsh treatment by commanding officers, his comrades had established a »soldier’s council«. The Reich court martial considered this a conspiracy against Germany, drawing a connection to the situation at the end of World War I, when revolutionary workers’ and soldiers’ councils instigated an uprising in November 1918. The court martial ignored the fact that substantial amounts of alcohol had come into play during meetings of the »soldier’s council« and that the soldiers had not carefully planned their actions, as would be the case for political organizations. Evidently the case was to constitute a cautionary example. As a former member of the socialist youth movement »The Falcons«, Johann Lukaschitz was sympathetic towards the »schemers«. He paid with his life for not denouncing them. On February 11, 1944, he was executed by guillotine in the Halle/Saale prison.

Literature

Baumann, Ulrich; Koch, Magnus (Hg.): »’Was damals Recht war… Soldaten und Zivilisten vor den Gerichten der Wehrmacht’. Begleitband zur Wanderausstellung der Stiftung Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas«, Berlin 2008.

Vogel, Detlef; Wette, Wolfram (Hg.): Das letzte Tabu. NS-Militärjustiz und Kriegsverrat, Berlin 2007.

»…I didn’t find the courage to voluntarily return to my unit.«

Anton Tischler (1912-1942)

Anton Tischler had enlisted in the Wehrmacht in April 1940 and was at first stationed in occupied France. In August of that year, his sister-in-law asked him to come home, as his wife Margarete (née Reiter) had fallen ill and needed his help. In reality, she wanted for nothing; she was simply afraid of losing her husband in the upcoming battles of World War II. Tischler didn’t return to his unit from the special leave he had been granted and managed to keep his support for his family a secret for nearly a year. He was most probably denounced by neighbors and arrested by military police in October 1941. He was able to avoid a death sentence only because his wife had repeatedly pleaded with him to stay with her. Margarete Tischler was comparatively harshly punished, receiving a 3-year prison sentence. Anton Tischler did not survive the war. He was deployed to a forced labor unit from the infamous Emsland camps in the northwest of the German Reich to the so-called »northern camps« in northern Scandinavia. Anton Tischler died there of the grueling conditions of imprisonment on November 2, 1942. He left behind his wife and their two children.

»…because otherwise she would have been sent to a concentration camp«

Erich Schiller (*1923)

In the winter of 1942, signalman Erich Feucht, who had been born in Lower Austrian Weitra, met Margit Stahl from Hungary in Berlin. She was afraid of being deported to a concentration camp, since according to the Nuremberg race laws she was considered a Jewish »Mischling«, so she asked him to help her. A few months later, Feucht helped her cross the border, after which he returned to Vienna and waited for a message from Budapest. When he did not hear from Margit Stahl, he set off for Budapest to make sure his acquaintance had arrived safely. Hungarian police arrested the 21-year-old and detained him for several months. The authorities eventually believed his story and he was granted a residence permit and a work permit. Feucht was arrested by a Wehrmacht patrol in Hungary just before Christmas 1943. The country had been Germany’s ally since 1941. The Division 177 court believed that Erich Feucht had acted out of compassion and sentenced him to 12 years in prison. He was deported to an Emsland camp and most probably survived the war.

»…humble and quiet, but unwavering in his beliefs«

Ernst Volkmann (1902-1941)

Ernst Volkmann had to die because he refused to fight for Nazi Germany on religious grounds. The deeply religious guitar maker, born in 1902 in Bohemian Schönbach (today Luby in Czechia), strongly resented National Socialism from its early days. In the 1920s, he moved to Vorarlberg and established himself there professionally. In 1929, he married Maria Handle from Bregenz, with whom he had three children. He ignored all Wehrmacht conscription orders, which is why Ernst Volkmann was arrested in June 1940. In 1941, the Reich court martial in Berlin took over his case.

Conscientious objection was considered a political crime. He stood by his religious beliefs until the end, seeing military service as a »violation of his moral freedom to defend himself against National Socialism«, for which the Berlin court sentenced him to death on July 7, 1941. A month later on August 9, at 5:05 am, Ernst Volkmann was beheaded in the Brandenburg-Görden prison. Until today, his name is engraved on the Bregenz war memorial honoring those killed in action during the world wars. From 1958, his fate was indicated at the church opposite the memorial; in 2010, a commemorative stele was dedicated to Ernst Volkmann in the vicinity of the war memorial.

Literature

Meinrad Pichler: »Nicht für Hitler«. Der katholische Kriegsdienstverweigerer Ernst Volkmann (1902–1941). In: Emerich, Susanne; Buder, Walter (Hg.): Mahnwache Ernst Volkmann (1902–1941). Widerstand und Verfolgung 1938–1945 in Bregenz, Feldkirch 2005, S. 6–11.

»…I left my unit and thought that I’d like to go home«

Johann Kuso (1923-1990)

In April 1943, Johann Kuso, an airplane mechanic from Steinbrunn in Burgenland, left his unit, which at the time was stationed at a military training area in Slovakia. He was captured a mere two days later, and during his interrogation he said that he had fled out of fear of punishment for a guard duty misdemeanor. Moreover, Kuso did not get along with the »comrades« in his unit. According to the military penal code, an absence of up to three days was considered an »absence without leave«, which usually resulted in shorter prison sentences. Yet Vienna’s Division 177 court classsified Johann Kusos’ absence as desertion, meaning a deliberate and permanent absence. His brief training and the short period of absence were considered mitigating circumstances. Nevertheless, a prison sentence entailed removing the convict from the Wehrmacht and handing him over to the civil judiciary. Internment usually took place at the infamous Emsland camps in the northwest of the »Greater German Reich«, where prisoners had to carry out hard forced labor in conditions reminiscent of a concentration camp. Unlike many of his fellow prisoners, Johann Kuso survived. He returned to his hometown and ran a tobacco kiosk. Johann Kuso later moved to Vienna, where he died on March 13, 1990.

»Now this is just stupid…«

Anton Brandhuber (1914-2008)

Anton Brandhuber, a farmer from Laa an der Thayer in Lower Austria, deserted from the Soviet front in February 1942. The 45th infantry division, which had been formed in Austria, had suffered severe losses outside of Moscow and was to be replenished with new soldiers from home. Brandhuber left his unit before it had reached its furthest position. His 10-day flight took him all across Europa to Feldkirch on the border between Austria and Lichtenstein. On February 27 he managed to get past the heavily secured fence system across the border to Switzerland. During questioning he stated for the record that the conditions upon arrival in Orjol – extreme cold, insufficient provisions and a bleak spirit among the soldiers – had been the immediate cause of his flight. The Swiss officer interrogating him wrote of his motives: »The interviewee claims that hopelessness for the future as well as the compulsion to fight for a regime he as an Austrian loathes are the main reason for his flight.« After the end of World War II, Anton Brandhuber returned to Austria. He lived on his farm in Laa an der Thaya until his death on August 28, 2005.

Literature

Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung (Hg.): Verbrechen der Wehrmacht – Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges 1941 – 1944. Ausstellungskatalog, Hamburg 2002.

Koch, Magnus: Fahnenfluchten. Deserteure der Wehrmacht im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Krieg in der Geschichte, Bd. 42, Paderborn 2008.

»So they said they wanted to have their arms broken«

Maria Musial (1919-2012)

The hairdresser Maria Lauterbach was born in 1919 to a working-class family of ten in Simmering. In the 1930s, the Musial family was active in the communist resistance movement: at first against the Austro-fascist regime, then against the National Socialists after 1938. In 1942, Maria married the trained machine fitter and officer of the Luftwaffe (German air force) Ernst Musial. Together they helped soldiers who did not want to fight to evade serving in the Wehrmacht – by deliberately inflicting bone fractures. Maria procured the necessary anesthetics from a doctor she knew. News of a conspicuous increase in cases of broken arms reached Karl Everts, chief judge in Vienna’s Division 177, at the turn of 1943/1944. He used an informer and eventually arrested the entire network in the summer of 1944. Maria’s nephew Karl Lauterbach and 13 other members of the Viennese »self-mutilation network« were executed for »undermining the military forces«; Maria Musial was sentenced to six years in prison, her husband to 12 years. Both survived to see the end of the war, though Ernst Musial was soon unable to work due to the long-term effects of his time in prison. Maria took care of him and had to give up working as a hairdresser. She remained politically active and was one of a group of survivors of Nazi military justice whom the committee »Justice for victims of Nazi military justice« invited to an annual commemoration in Kagran’s Donaupark from 2002 on. Maria Musial died in 2005.

Literature

»I always feel that I am a human first, then a Pole«

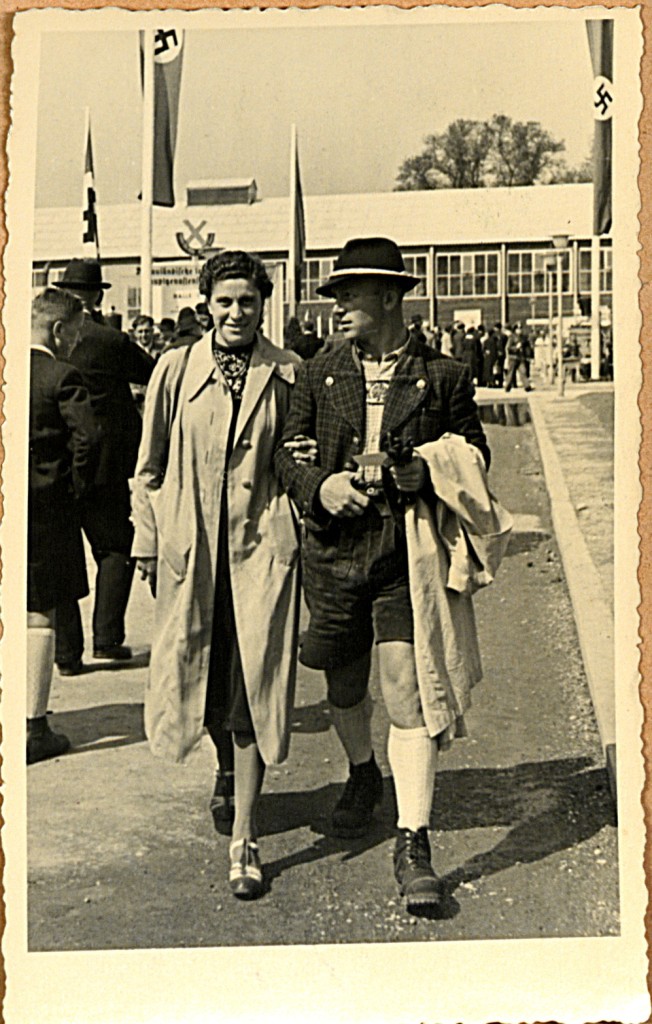

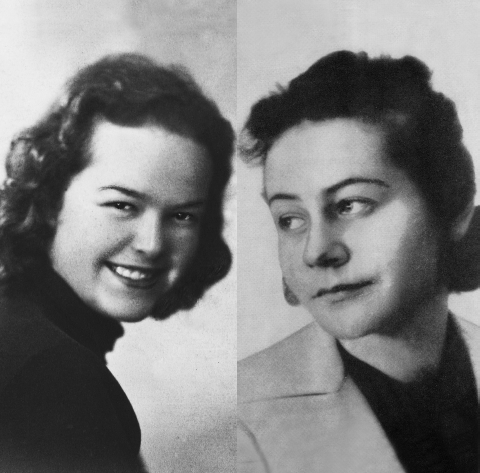

Krystyna Wituska (1920-1944) und Maria Kacprzyk (1922-2011)

Maria Kacprzyk und Maria Wituska, um 1940.

Quellen: Privatarchiv Maria Kacprzyk, Danzig sowie Universytecka w Warszawie

On September 1, 1939, the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland. For the Polish population, daily life was characterized by raids, arrests and executions. Many were deported as forced laborers to serve the German wartime economy. Krystyna Wituska, the daughter of an estate owner, and Maria Kacprzyk, who came from a family of entrepreneurs, decided to put up resistance to the oppression. They were given the task of gathering information about the occupation forces. When their resistance network was uncovered, the young women were arrested in October 1942 and transferred to Berlin. On April 19, 1943, Werner Lueben, senate president at the Reich court martial, sentenced Krystyna Wituska to death for espionage, preparations for treason and aiding the enemy. Her friend Maria was sentenced to eight years in a harsh penal camp. She survived the war, while Krystyna Wituska was executed by guillotine on June 26, 1944 at the behest of the Reich court martial. After 1945, Maria had a hard time coming to terms with the loss of her friend and suffered of depression for a long time. She studied medicine, went to acting school, worked as a tour guide, got married and had two children. In the 1980s, Maria Kacprzyk was active in the Solidarność movement, which sought Poland’s democratization and its disengagement from the Warsaw Pact. She died on April 4, 2011 in Gdańsk.

Literature

Skowronski, Lars; Trieder, Simone: Zelle Nr. 18. Eine Geschichte von Mut und Freundschaft, Berlin 2014.

»…because the others pestered me too much«

Alois Tiefengruber (1912-?)

When Alois Tiefengruber, who had been born in Graz, had to join the Wehrmacht in September 1942, he could hardly look back on a well-adjusted life: he had never met his father and had lived with foster parents already before the untimely death of his mother. Problems at school were followed by health constraints. Since the age of seven, Tiefengruber had suffered epileptic fits, which led to psychiatric examinations and hospital stays. He became addicted to alcohol. In the army, he quickly became a source of irritation in his unit, as he wouldn’t or couldn’t deal with the military drill. He left his unit after only a few days, stating that he had been excluded and tortured by his »comrades«. On his 30th birthday he was initially sentenced to ten years in prison for desertion and »recidivist theft«. Since the sentence was not confirmed by the Army High Command, the court tried the case anew; despite the prosecution’s demands, there was no death sentence, probably because of Tiefengruber’s health issues. Such leniency was rare in similar cases before Wehrmacht courts. Tiefengruber was sent to a field penal camp – the harshest form of imprisonment within the Wehrmacht – and it is not known whether he survived.

Literature

Baumann, Ulrich; Koch, Magnus (Hg.): »’Was damals Recht war… Soldaten und Zivilisten vor den Gerichten der Wehrmacht’. Begleitband zur Wanderausstellung der Stiftung Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas«, Berlin 2008.

Baumann, Ulrich: »Wo sind die Deserteure?« Öffentliche Meinung und Debatten über Verurteilte der Wehrmachtjustiz in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1949-1998. In: Pirker, Peter; Wenninger, Florian (Hg.): Wehrmachtsjustiz. Kontext, Praxis, Nachwirkungen, Wien 2010, S. 270-285.

Forster, David: Die militärgerichtliche Verfolgung von Verratsdelikten im Dritten Reich. In Manoschek, Walter (Hg.): Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich, Wien 2003, S. 238-253.

Fritsche, Maria: Entziehungen. Österreichische Deserteure und Selbstverstümmler in der Deutschen Wehrmacht, Wien 2004.

Fritsche, Maria: Feige Männer? Fremd- und Selbstbilder von Wehrmachtsdeserteuren. In: Ariadne 47 (2005), ‘Kriegsfrauen und Kriegsmänner’. Geschlechterrollen im Krieg, S. 54-61.

Fritsche, Maria: Österreichische Opfer der NS-Militärgerichtsbarkeit. Grundlegende Ausführungen zu den Untersuchungsergebnissen. In: Manoschek, Walter (Hg.): Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich, Wien 2003, S. 80-103.

Fritsche, Maria: Die Verfolgung von österreichischen Selbstverstümmelern in der deutschen Wehrmacht. In: Manoschek, Walter (Hg.): Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich, Wien 2003, S. 195-214.

Fritsche, Maria: »Goebbels ist der größte Depp«. Wehrkraftersetzende Äußerungen in der deutschen Wehrmacht. In: Manoschek, Walter (Hg.): Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich, Wien 2003, S. 215-237.

Geldmacher, Thomas u.a. (Hg.): »Da machen wir nicht mehr mit«. Österreichische Soldaten und Zivilisten vor Gerichten der Wehrmacht, Wien 2010.

Geldmacher, Thomas: »Auf Nimmerwiedersehen!« Fahnenflucht, unerlaubte Entfernung und das Problem, die Tatbestände auseinanderzuhalten. In: Manoschek, Walter (Hg.): Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich, Wien 2003, S. 133-194.

Haase, Norbert: Von »Ons Jongen«, »Malgré –nous« und anderen. Das Schicksal der ausländischen Zwangsrekrutierten im Zweiten Weltkrieg. In: Haase, Norbert; Paul, Gerhard (Hg.): Die anderen Soldaten. Wehrkraftzersetzung, Gehorsamsverweigerung und Fahnenflucht im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt 1995, S. 157-173.

Koch, Magnus: Fahnenfluchten. Deserteure der Wehrmacht im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Krieg in der Geschichte, Bd. 42, Paderborn 2008.

Koch, Magnus: Prägung – Erfahrung – Situation. Überlegungen zur Frage, warum Wehrmachtssoldaten ihre Truppe verließen. In: Kirschner, Albrecht (Hg.): Deserteure, Wehrkraftzersetzer und ihre Richter. Marburger Zwischenbilanz zur NS-Militärjustiz vor und nach 1945, Marburg 2010, S. 149-162.

Reemtsma, Jan Philipp: Wie hätte ich mich verhalten? Gedanken über eine populäre Frage. In: Ders. »Wie hätte ich mich verhalten?« Und andere nicht nur deutsche Fragen, München 2001, S. 9-29.

Rothmaler, Christiane: »…weil ich Angst hatte, daß er erschossen würde«. Frauen und Deserteure. In: Ebbinghaus, Angelika; Linne, Karsten (Hg.): Kein abgeschlossenes Kapitel: Hamurg im »Dritten Reich«, Hamburg 1997, S. 461-486.

Walter, Thomas: Die Kriegsdienstverweigerer in den Mühlen der NS-Militärgerichtsbarkeit. In: Manoschek, Walter (Hg.): Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich, Wien 2003, S. 114-132.

Weitere Sammlungen von Biografien von Verfolgten bieten folgende Instiutionen an:

Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstands