PERPETRATORS

Around 3,000 judges served in the Wehrmacht during World War II. They presided over three million trials, especially against German soldiers, but also against prisoners of war and civilians from Germany and abroad – in cases where the offense was of military relevance.

Wehrmacht Military Justice and Warfare

The judges’ task was to punish offenses with quick and harsh sentences; their two guiding principles were deterrence and »education« (in the case of members of the Wehrmacht). The »maintenance of discipline« among the troops was of utmost importance. The vanguard of the Wehrmacht judiciary defined their role as that of a »sharp sword in the hands of the leadership set to achieve victory«. The law was to serve the armed forces.

The Demand of Partisanship

This objective is best illustrated by the symbol the National Socialists gave their judiciary (both civilian and military) after seizing power in 1933. Following the Roman tradition of personifying the law in Justitia, Nazi law is not depicted as a virgin, but as an eagle, the German heraldic animal. Yet it isn’t the eagle of the German Reich, as one might assume, but the eagle of the National Socialist Party (which faces left). The law in the German Reich was therefore not to be an issue of the state, but of the party – both partisan and partial law. The lack of a blindfold, as worn by Justitia, was deliberate: her bound eyes represent the impartiality of justice, judging without looking at the accused. The party eagle can see clearly, and therefore represents partiality. This is amplified by the swastika, the symbol of the party and the state, in the center of the crest. The picture is rounded off by a grotesquely large (executioner’s) sword, on which the eagle is perched; it stands for a harsh judicial practice characterized by deterrence.

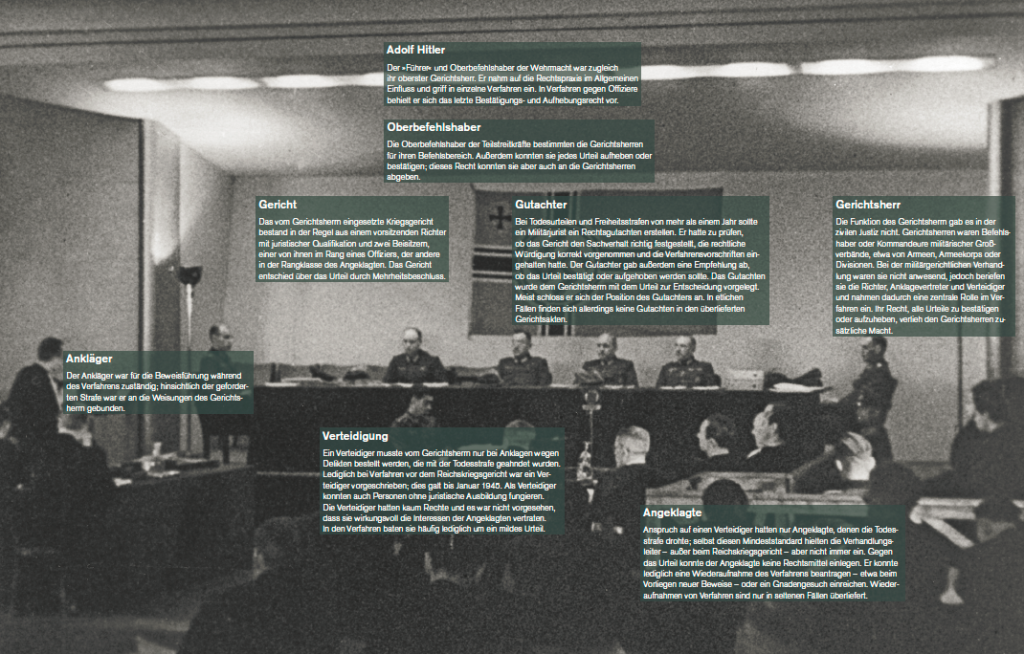

Übersicht: Rollen und Funktionen an Wehrmachtgerichten entlang den Bestimmungen der Kriegsstrafverfahrensordnung.

Quelle: Stiftung Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas

Reasons for the Sentencing Record

Current research shows that most military judges willingly meted out harsh sentences. There are many reasons for this. For one, it is likely that they strongly agreed with the principles of the »Führer state« and the wartime objectives of the Nazi regime. As records show, careerism, peer pressure or judicial esprit de corps were more important that isolated qualms about the harsh sentences in demand. The course of the war too influenced the judgments: In order to avert the defeat that had been looming since 1943, Wehrmacht justice proceeded ever more brutally against »signs of disintegration«, regardless of whether it was a case at home or on the front.

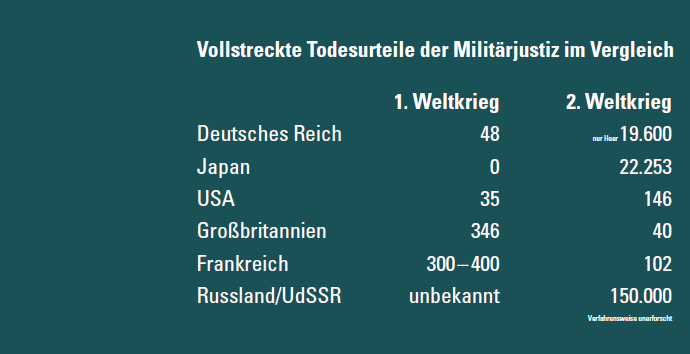

Tabelle Urteilsbilanz Militärjustiz im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg

Quelle: Stiftung Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas

Case Studies Wehrmacht Judges

The justice corps of the Wehrmacht has hardly been researched to date. It is estimated that there were between 200 and 300 Austrian judges among its ranks. Whether their specific legal practice differed from that of their »Reich German« colleagues is not known. By analogy with the research on attitudes and motivations of the approximately 1.3 million Austrians in the Wehrmacht, it is possible to assume that Austrian judges conformed to the war effort just as seamlessly as their armed comrades did.

The following examples of Austrian and German Wehrmacht judges (only available in german) illustrate a spectrum of functions, positions and possible courses of action. While Heinrich Hehnen, a conservative, German-national judge from Cologne, exemplifies a milder sentencing and assessing practice, Karl Everts from Vienna’s Division Court reveals a contrary course of action. Both were chief judges in their respective divisions, and both interpreted their tasks differently – the jurists were still left with argumentative leeway, despite the special situation caused by the war and the strict control by the often ruthless military supervision. It was even possible to use this leeway to the benefit of the defendants.

The presentation of Austrian judges shows that research on this theme is commencing in Austria. The case of Otto Tschadek serves as an example of both the sentencing practice and the personal and public discourse surrounding the topic during the Second Republic. Although his function as a navy judge was no secret, his apologetic and euphemistic self-appraising statements sufficed to positively depict both himself and all military judges from the »Third Reich« as people who had »fulfilled their duties« and served as defenders of the homeland.